The Wonder Years, Memory, and Mourning

For now, I’ll take my grieving in 30-minute journeys to my past.

By AMANDA ANN KLEIN

In 1988, I was 12 years old. I was a 6th grader at the Susquehanna Township Middle School. I lived in the suburbs. I had never kissed a boy. I wore giant Sally Jesse Raphael-style glasses and every day was a bad hair day. In other words, I was a pretty typical 12-year-old kid.

Therefore, despite our gender differences, I felt a strong kinship with Kevin Arnold (Fred Savage), the protagonist of The Wonder Years.

Kevin was also a typical 12-year-old kid: he was alternately moral and selfish, brave and cowardly, kind and cruel. He knew better than to question his parents and teachers, but he did it anyway, and suffered the consequences. He had an older brother who tortured him and a father who worked a lot and said very little. He was grappling with an adult world he only partially understood, but felt its ramifications as strongly as any adult.

Kevin was me, only in a boy’s body.

The Wonder Years: A Recap

If you are unfamiliar with this program for some reason, The Wonder Years was a 30-minute comedy/drama that ran on ABC from 1988–1993.

The series opens in 1968, when protagonist Kevin Arnold (Fred Savage) is starting junior high. Throughout the series, Kevin’s personal coming-of-age story runs parallel with America’s very different, public coming-of-age story.

As Kevin becomes more of an adult, America is also coming to terms with a new kind of adulthood: Vietnam, second-wave feminism, the Black Power movement, hippies, free love, a man on the moon. You get the picture.

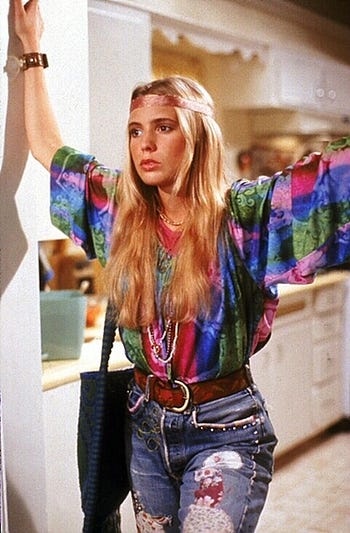

In episode 4, “Angel,” Kevin’s older sister, Karen (Olivia D’Abo), introduces the family to her radical boyfriend, Louis (played by a very young, very handsome John Corbett). Kevin takes an instant dislike to Louis because he makes out with his sister on his parents’ lawn (gross!) and because, as Kevin’s voiceover explains, “I don’t know what it was about Louis that I didn’t like. Guess there was something about him I didn’t understand.”

Here we catch a glimpse of Louis’ spray-painted VW van, with the words Somethings Happening scrawled on the door. To Kevin, those words were ciphers, shorthand for a movement that he was too young to comprehend. Louis and his leather vest and VW van were something, to use Kevin’s words “that [were]…taking my sister away from us.”

When I watched this episode at age 12, those words were also meaningless to me. A spray-painted van and long hair signified “hippie,” but I didn’t actually know what a hippie was. To me, “hippie” was a costume worn at Halloween rather than a representative of a political movement.

What I didn’t know then is that in 1968, a younger generation was beginning to question the way the world worked. They saw their parents as sleep walkers, as drones who had yet to be enlightened about “what’s going on.”

For example, in the same episode, Louis has dinner with Kevin and the rest of the Arnold family. When Norma (Alley Mills), Kevin’s mother, mentions that the son of a family friend was recently killed in Vietnam, a heated conversation ensues. Start at 14:30.

When I watched this scene in 1988, I don’t think I understood the nuances of the argument. I saw it much the same way that Kevin sees it: one more fight in a long string of fights he has witnessed between his sister and his parents.

But when my husband and I recently rewatched The Wonder Years on Netflix, I was struck by the honesty of this scene.

It would have been easy to make Jack an out-of-touch defender of the old guard holding on to his ideals, even as he sees them crumbling around him. Yet, Jack is sympathetic here and so is his point of view. He fought in Korea. He served his country. Now he is enjoying his reward (or trying to): a comfortable home in the suburbs with his wife and children.

When Louis, who could also come off as a radical caricature but doesn’t, begins to poke holes in Jack’s worldview, there is a sadness there. Louis is not enjoying this argument. You can feel that Louis is angry, which we expect, but what I love about this scene is that it also legitimizes Jack’s anger.

When he snaps, “What do you know about it?! Who the hell are you to say that?!” you can feel the rage and betrayal of Jack’s generation. How does this hippie know anything about the way the world works? Where is his authority to speak? And why is his hair so damn long?

This scene was just one of many that has resonated with me in new ways since I began rewatching The Wonder Years, some 24 years after it first aired. This experience has resulted in a doubled viewing position.

My Doubled Viewing Position

On the one hand, I am watching as a 35-year-old and so the historical and cultural touchstones that I missed when I was 12 — the changing meaning of the suburbs in America in the 1960s, the anti-war movement, the student protests of 1968, The Feminine Mystique — are suddenly visible and significant.

But at the same time, as I watch, I am still watching as a 12 year old.

When I sat down to watch the pilot episode on Netflix, and the opening credits began to play, I felt crushed — not by nostalgia, but by the weight of being 12. Those credits, a faux-scratchy home movie of Kevin Arnold and his family enjoying their last days of innocence, were etched onto my brain so that each frame was a surprise and a memory.

This experience was like reliving entire pieces of my adolescence (complete with the attendant emotions) while simultaneously having the ability to contemplate these pieces of my youth from the detached perspective of an adult.

When I was 12 I so strongly identified with Kevin Arnold that when Winnie Cooper walks up to the bus stop in the pilot episode, having shed her pigtails and glasses for pink fishnet stockings and white go-go boots, I too, fell madly in love with her.

Even at 35 I was hit by that excruciating longing and terror so characteristic of 12-year-old desire. I was in the past and the present at the same time.

Because of this doubled viewing position, revisiting The Wonder Years has been therapeutic for me.

You see, almost three months ago, my father died. I will not say that he “passed away” since this term implies a softness, like falling asleep or slowly vanishing. Death can be like this, but this was not my experience of it.

When I returned to my regular life, after the funeral and the sad faces and the conversations I didn’t want to be having, I encountered a steady stream of condolence notes, tentative e-mails, and awkward conversations with well-meaning colleagues about my winter break. One condolence note in particular stood out to me. Here is what it said:

“My Dad died when I was 30. I remember being surprised at how his death could make me feel like a child again.”

This note made me think about my experiences sitting in my father’s beige hospital room with my mother and brother. As we sat there together I realized that it had been almost a decade since the four of us had been alone together — no spouses, no children, no reminders of the lives that we had built apart from the original family unit.

Whether we liked it or not, the three of us were transported back to an earlier time in our lives and into roles we had long since abandoned. I was once again a daughter and a sister rather than a wife and mother. I suddenly felt like a child again.

Finding Comfort in the Past

Perhaps this is why, some three months later, I have been finding so much comfort in the past: looking through old photo albums, creating Pinterest boards chronicling my youth, and yes, rewatching shows from my childhood, like The Wonder Years.

This choice is fitting, in a lot of ways, since almost every episode of The Wonder Years contains a shot, or an entire scene, that focuses on the Arnold family watching television. These scenes focus on iconic TV moments, of course, such as when Kevin and his family watch the crew of the Apollo 8 orbit the moon.

But we also see the family in more mundane television-viewing scenarios. The TV is a way for the family to bond and a way for them to escape from each other. In the pilot Kevin even addresses the primacy of television after experiencing one of the most important landmarks of his adolescence: his first kiss.

These words are a defense of suburban life with its “little boxes made of ticky tacky,” but they are also a defense of television watching itself.

Kevin argues that although his generation seems to be living in identical houses and watching indentical shows on their indentical TV sets, that doesn’t mean that their experiences of the world aren’t unique, meaningful, and real.

For Kevin, TV doesn’t detract from his reality. It is a meaningful part of his reality. Mine too.

***

When people write about a moment in the present sending them back in time, they almost always cite Marcel Proust’s seven-volume novel, Remembrance of Things Past (1913–1927). There’s a reason for the ubiquity of Proust quotes in writings about memory: the dude nails it.

So here’s Proust talking about how eating a madeleine cookie and a hot cup of tea generated an “involuntary memory”:

Rewatching The Wonder Years performed the same spell on me as Proust’s madeleine did on him.

Take for an example, the episode, “My Father’s Office,” in which Kevin attempts to understand why his father is so tired and grumpy when he comes from working his job as a middle-management drone in an ominous-sounding place called NORCOM.

After asking his father a few questions and receiving only unsatisfactory answers, Kevin agrees to go to work with him for the day. He sees that his dad has a lot of power, which makes him proud, but that he must also answer to a needling boss, which embarrasses him slightly.

Over the course of the day, Kevin comes to understand that the trials his father endures everyday have nothing to do with being his father. He also learns that his father once wished to be a ship’s captain, navigating his vessel by watching the stars. This blows Kevin’s mind.

The episode concludes with Kevin’s joining his father in their yard to look at the stars. Up until this point, star-gazing had been something Kevin’s father did alone, when he was angry or frustrated. Kevin often watched him do this through the window with a mixture of curiosity and fear. But at the end of this episode, Kevin joins his father and they share this experience while strains of “Blackbird” play on the soundtrack.

Of course, as Kevin points out, understanding comes with a price: “That night my father stood there, looking up at the sky the way he always did. But suddenly I realized I wasn’t afraid of him in quite the same way anymore. The funny thing is, I felt like I lost something.”

I’ll admit that at age 12 I did not quite understand the meaning of Kevin’s epiphany (he always concluded the episode with an epiphany well beyond his young age). I, too, had a hard time seeing my father as a “real person” but I didn’t see why such an understanding would also be a loss. In fact, it has only been in the last few years, as I’ve watched my father’s body deteriorate and his attendant anger and humiliation, that I understood what Kevin Arnold meant.

He meant that when we are able to see our parents as something other than a servant of our needs, our relationship with them changes. Once we realize that our parents have feelings and desires that have nothing to do with us, we understand them better. They become people, rather than parents.

But we also lose a piece of our childhood once we gain that understanding. This is a loss that needs to be mourned. And sure enough, as the credits rolled on “My Father’s Office,” I cried.

Over the last few months, I have been stumbling through my own grief. I thought it would move in a straight line, but it moves in circles, disappearing and returning. When the grief moves away, I enjoy the freedom and respite. But when it circles close I try to grab it and confront it.

It may sound strange, but the involuntary memories evoked by The Wonder Years are helping me to work through my grief and bring it close. Here’s Proust again:

The Wonder Years is filled with such remembrances, structures of feelings I have long forgotten and which I doubt I could access in any other way. We all mourn in our own ways and in our own time.

For now, I think, I’ll take my mourning in 30-minute journeys to my past, when my parents were both still my “parents” and when I had not yet become a parent myself.

For some, nostalgia can be toxic and overwhelming but for me, right now, it is as comforting as a plate of madeleines, a cup of hot tea, and a seat on the couch in front of the glowing box.

Originally published at judgmentalobserver.com.

If you enjoyed this, please hit the green “Recommend” button below so others might also enjoy it.

Follow THE OUTTAKE: Medium | Twitter | Facebook